Critique of “Osmo” as an Educational Tool

There is a burgeoning need for students to possess the capacity to think creatively in future workplaces that will possess a host of demands distinctly different to the ones we have experienced over the recent and distant past (Pink 2011). To operate within the complex environmental, social and economic pressures of the twenty-first century, students must be creative, innovative, enterprising and adaptable (ACARA).

Creativity is accepted among scholars as the generation of ideas that combine originality and task appropriateness (Beghetto & Kaufmann 2013). Students learn to think creatively as they generate new knowledge, seek possibilities, consider alternatives and solve problems (ACARA). Teaching these capabilities to children can prove challenging at the best of times, but there exist technological aids to assist teachers.

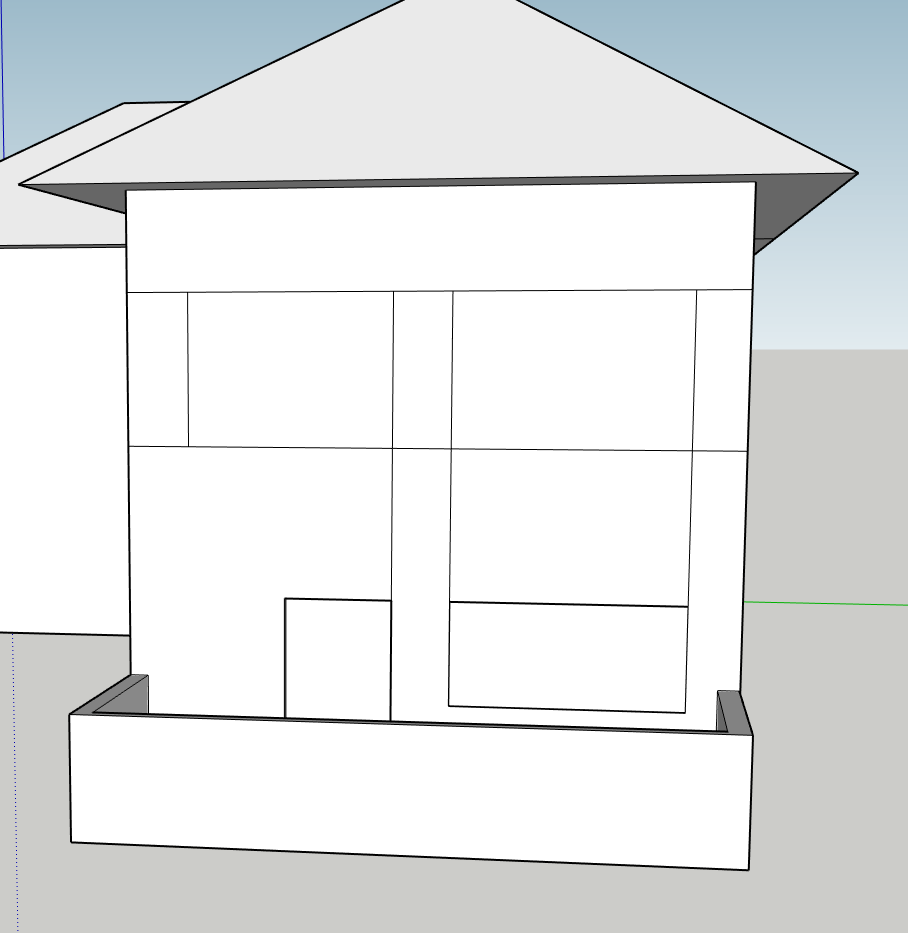

Osmo – Digital Learning in the Real World

Retrieved from https://www.playosmo.com/en/words/

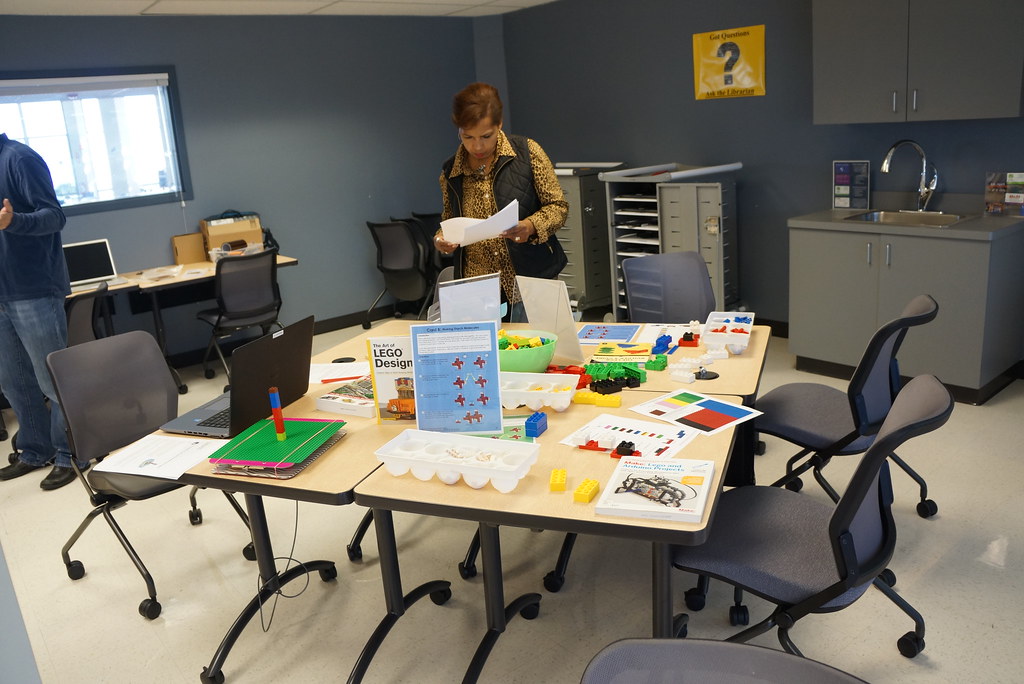

Retrieved from https://gethacking.com/blogs/news/osmo-genius-kit-review-play-smart

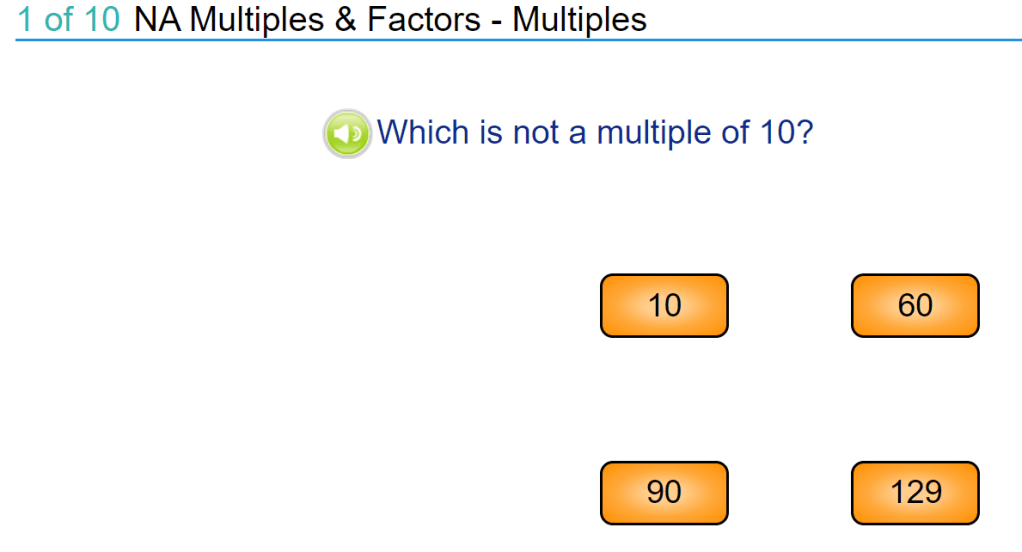

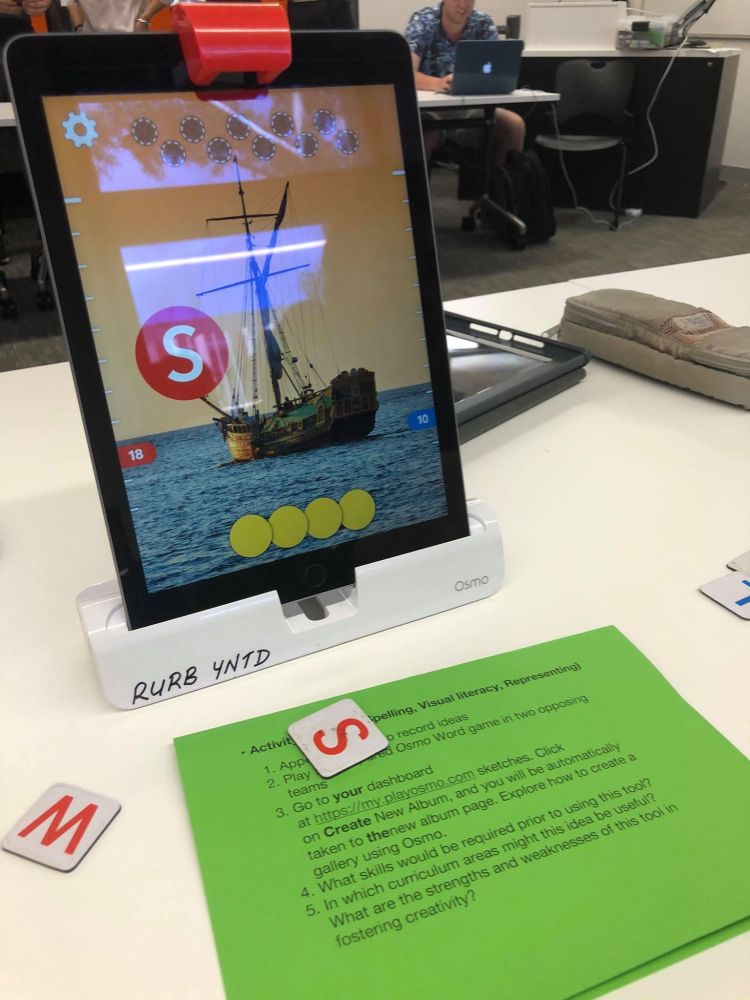

Osmo is a digital tool for iPad that combines images and sounds with tactile tools such as letter tiles. Using a stand and mirror placed over the camera, Osmo can recognise objects placed in front of the screen enabling student’s real-life experiences to overlap into the digital space. The game we played required us to place letter tiles in front of the screen in order to spell out a word associated with an image displayed on the screen. Letters were either correct and placed into the corresponding space in a word or were incorrect and resulted in the loss of a chance, similar to the classroom classic “hangman”.

At a surface level Osmo may not appear to foster creative thinking simply by having students play the game, but it is possible for students to create their own image galleries and the words associated with each image. This process requires children to engage creatively with the content they are learning and generate associations specific to their own experience. In a secondary science classroom this could be used an effective revision tool, where students each make galleries of their own that they then share with others in the class. This approach benefits student learning by both requiring students’ active engagement (Obenland, Munson & Hutchinson 2012) with content in making image galleries of their own and exposing them to the ideas of their peers.

Through activities such as this, Osmo allows for the type of interactive engagement with curriculum content that will build student’s creative capacities and readiness for the future workplace. Osmo is, however, not cheap to provide on a whole class or year scale. iPads must be available for students to use in groups not larger than 4 and the starter kit itself retails for $167 AUD, placing it outside some schools’ reach.

Reference list

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). Critical and Creative Thinking. Retrieved at: https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabilities/critical-and-creative-thinking/

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2013). Fundamentals of Creativity. Educational Leadership, 70(5), 10-15

Obenland, C. A., Munson, A.H., Hutchinson, J. S., (2012) Silent Students’ Participation in a Large Active Learning Science Classroom. College Science Teaching, 42(2), 90-98

Pink, D. (2011). Creative fluency. In L. Crocket, I Jukes, A. Churches (Eds.), Literacy is not enough – 21st Century fluencies for the digital age. (pp. 43-54). Corwin

Triple S Games (2018). How to Play: Hangman. Retrieved at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cGOeiQfjYPk

Images are my own unless otherwise specified